A WARM, HIGH-SUMMER EVENING IN THE CITY found a good proportion of New York’s first-tier museum directors and curators present at the Guggenheim to hear a conversation with peripatetic Swiss curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, currently codirector of the Serpentine Gallery in London. Lisa Phillips, Glenn Lowry, and Thelma Golden were among those paying this compliment to their visiting colleague. (One important local director, who arrived without a ticket, was turned away from the sold-out event.) They and the quietly attentive crowd were rewarded with a rapid-fire but softly spoken seminar by Obrist, who was prodded by succinct questions from the museum’s director, Richard Armstrong, and chief curator, Nancy Spector, on the forgotten history of curating as both intellectual discipline and experimental art form, indeed as the primary object of a modern art history yet to be written.

The ostensible occasion for Monday’s event was the “relaunch” of Obrist’s 2008 book, A Brief History of Curating, composed from interviews he had accumulated since the 1990s with curators whose examples he saw as formative for his own practice. The names ranged from those with the renown of Pontus Hultén and Anne d’Harnoncourt to those of more esoteric reputation, like Jean Leering and Franz Meyer, who directed public collections in Eindhoven and Krefeld respectively, as well as collaborating on an influential Documenta exhibition each. Behind such figures, Obrist was at pains to emphasize, lay other, equally important innovators, whose contributions are in danger of slipping from historical consciousness altogether. An example he cited more than once was the late James Speyer of the Art Institute of Chicago, whose training in another field (architecture with Mies van der Rohe) Obrist finds to be a common thread among the true pioneers.

Fortunately for those who missed many of those names in the course of Obrist’s swift allusions, these genealogies can be reviewed at leisure in his book. He was more than clear, however, in insisting that the history of modern art, as construed by the museum and the academy alike, has been narrowly and uncritically limited to a history of objects, when it might be more fully understood as a history of exhibitions. He pointed out that exhibitions are not collected nor have they been documented with the consistency and depth that historical research requires, leaving in obscurity the work and imagination of curators who absorbed the lore of their elders and informally passed on their accumulated expertise to the succeeding generation: Only by comprehending those genealogies can we understand how some objects rather than others entered into conventional art history. In his recent experience, Obrist went on to say, the improvised discipline of curating has been straining against its confinement to the art world, offering a model of communication and the articulation of knowledge that is increasingly attractive to scientists, architects, and novelists.

Six of Obrist’s eleven interview subjects died before the book saw the light of day, and that fact lent the low-key passion of Obrist’s remarks both an urgent and an elegiac character. The Guggenheim has a special institutional interest in memorializing one of the departed, Walter Hopps, who organized its Robert Rauschenberg and James Rosenquist retrospectives from his base as adviser to the Menil Collection in Houston. Obrist places his exchange with Hopps at the beginning of his sequence of interviews, which made for a nice alignment of priorities between author and institution that evening. In a charming touch, event co-organizers ForYourArt distributed to the audience reproductions of the badge reading WALTER HOPPS WILL BE HERE IN TWENTY MINUTES, which his staffs at the Pasadena Museum of Art, the Corcoran, and the Smithsonian once wore with a mixture of exasperation and pride.

The conversation had indeed been announced as an opportunity to hear all three participants reflect on Hopps’s legacy, though there were some listeners lingering at the reception afterward who felt that the designated man of the hour had never really arrived as a vivid presence in the discussion. Not that Obrist was stinting in his praise, particularly for Hopps’s ability to conceive an exhibition as a “self-organizing” entity, notably in the 1978 “Thirty-Six Hours” exhibition in Washington, where Hopps announced that he would hang any work brought to the venue (the Museum of Temporary Art) during the titular time frame of the show—an example Obrist said was kept securely in his own “toolbox” of ideas. It is also more than clear that Obrist shares with Hopps a fearless drive to take chances and confound categories, combined with a warmly inclusive generosity toward valid artmaking at all levels and in any medium.

For an audience that skewed toward the young, however, it might have been illuminating to spend a little more of the allotted time bringing out the essential style of Hopps as counterweight to the ever-present forces of institutional conformity. Some pictures might have helped: During the ’60s, when his peers embraced the counterculture, he always wore a suit and tie. Those who knew him best called him Chico, a link to his physician father’s expatriate years in Mexico. In his later years, as museum-executive style had veered toward aping the sartorial armor of Wall Street and corporate trustees, Hopps went casual with a broad-brimmed hat that brought out the charro evoked by his youthful nickname. The tall, angular presence; the even, never ruffled speech; the deep well of experience behind nearly every utterance: It would take Clint Eastwood in glasses to play him. Even a shadow of that Hopps would have been worth just about any wait. |

IT TAKES GUTS to specify “flaming” as a dress code in the Hamptons, but the annual benefit for Robert Wilson’s Watermill Center, a “laboratory for performance” tucked away near Southampton, is a sufficiently established date on the local social calendar (this was the sixteenth installment) that a crowd is assured no matter what the sartorial stipulation. Even so, while many guests at Saturday evening’s “Inferno” shindig made at least a nod toward the too-hot-to-handle theme, a few went to the opposite extreme; The Whitney’s Shamim Momin, Participant Inc.’s Lia Gangitano, and performance-art poster girl Marina Abramovic, for example, had evidently abandoned the attempt to unearth anything but basic black in their summer wardrobes. Others, like MoMA’s Klaus Biesenbach, clad in powder-blue linen, went for lighter but similarly cool alternatives. (Among those who did try: writer Jay McInerney and Real Housewife countess LuAnn de Lesseps.)

Required first to negotiate Sue de Beer’s Ring of Trees—the installation was set on a floor of loose rocks that sent those clad in high heels (of which there were many) flailing for support—guests emerged onto the center’s expansive rear courtyard, where one marquee, housing auction lots, faced off against another, marked for dinner. While fuel in the form of cocktails was dispensed, an oddball lineup of carnivalesque happenings opened with a fire eater and continued with a group of children clustered into the form of a giant spider. Riverbed Theater’s quieter intervention, Flowers of E, occupied the roof of an ancillary building, as a torch-lit wooded area at the property’s far end was dotted with further diversions. Perhaps most absorbing of these, if only for its incongruous austerity, was a performance that combined drama, dance, and music in a stark, ritualistic style for an audience split between those earnestly scribbling notes and those just looking worried.

“Certain critics hated it, certain critics loved it.” Back by the auction tent, which was starting to look busy by seven or so, Stetson-wearing musician Rufus Wainwright was holding court about his own recent output and anticipating his upcoming set at the Watermill’s “Last Song of Summer” gig in August. Masked by shades, critic James Trainor kept a somewhat lower profile, while Team Gallery’s Alex Logsdail played us an alarming iPhone slide show that pictured his own eyes ringed with bruises, the now-faded results of a recent accident.

Wandering over to the dinner tent for a reccy, I was treated not to the sought-after meal, but to sundry exchanges perhaps more representative of those who had actually paid to be there. “A friend of ours just moved into an artists’ co-op on Sixty-seventh Street,” one senior gent was telling his party. “A neighbor came by and introduced himself as ‘Paul.’ Turned out it was Paul from Peter, Paul, and Mary!” “Oh yes,” one of his audience responded brightly, “we know him too!” “Supposedly David Bowie is here—have you seen him?” a twinkly white-haired man asked me as I took a seat beside him and his wife for a quick overview. I confessed that I hadn’t. “The de Menils are around, though,” he advised me. “Lovely people.” Admiring Yochai Matos’s fluorescent-tube installation Flame Gate, we both confessed to having mistaken it for a Dan Flavin at first look. “We used to go to his Halloween parties,” he recalled. “Bit of a grumpy guy.”

As the bell finally rang for chow, we trailed into the big-top-like enclosure. With no obvious logic to the seating, I found myself opposite genial Puerto Rican artist Enoc Perez and his wife, jewelry designer Carole Le Bris. By my side was an aloof benefit regular named Chad, accompanied by a female friend with the flamboyant moniker of Stormy, clearly the target of his interest that night. As artist C. Ryder Cooley performed aerial acrobatics against a projected backdrop, purportedly “invoking visions of human and animal interrelations in response to times of violence and war” but tending more immediately to elicit comparisons with Cirque du Soleil, host Jorn Weisbrodt introduced testimonials from some of Watermill’s other past and current (and future) artists-in-residence. Wildly varied in style and content but uniformly disarming, these veered in one bizarre case into an unexpected and deafening rendition of “That’s the Way I Like It.” Only Robert Wilson himself came close in terms of strangeness, his own speech ending on a non sequitur about Jessye Norman, followed by an out-of-nowhere but heartfelt “Yes, we can!” |

POSTERS PRONOUNCING AI WEIWEI THE MOST EVOCATIVE CREATOR IN CONTEMPORARY CHINA greeted me as I alighted through the Roppongi subway station last Friday at the end of a long journey from New York, having arrived in Tokyo just in time for the opening of Ai’s exhibition “According to What?” at the Mori Art Museum. As I checked into my hotel and changed, I pondered whether evocative had been a last-minute substitution for provocative—the latter would have been appropriate given Ai’s recent troubles with the law—or whether Japanese English just skews toward these sorts of poetic declarations. As with many things about Ai Weiwei, it’s an ambiguity best preserved.

The exhibition, organized by chief curator Mami Kataoka and spread across the Mori’s entire exhibition space, chronicles the breadth of Ai’s work more completely than any other to date. Mutations of Chinese “cultural readymades” like furniture and pottery lead to original riffs on those same forms, which lead to architectural models and grueling Warholian films in a familiar enough progression. The only major new piece was as much political manifesto as aesthetic investigation, and more provocation than evocation: An assemblage of backpacks hung from the ceiling in commemoration of the schoolchild casualties of last year’s Sichuan earthquake.

Ai huddled in the final gallery, receiving well-wishers until museum staff herded the crowd downstairs for a long round of speeches in translation. (For all their professed animosity, Japan and China share a common love for such prelection. In China, however, such ceremonies take place before the exhibition, and certainly not over champagne.) The crowd would erupt in waves of rowdiness, prompting the Mori’s dedicated shusher to action, a cause-and-effect familiar to anyone who had attended the opening of Francesca von Habsburg’s collection show a few months prior.

If you’ve never been to the Mori, or to the Roppongi Hills complex that it crowns, don’t believe the bit in Rem Koolhaas’s Content about the place titled “Pure Evil.” “A project of unmitigated awfulness that embodies, with seeming deliberation, a recapitulation of everything bad about twentieth century architecture,” he called it back in 2003, the year it opened. Sure, it’s a bland triumph of site-unspecific commercial architecture that harks back to an optimistic world in which lots of time was spent looking for wi-fi hot spots. But these days, that’s not such a bad moment to revisit, and as a staging of the anxieties (and guilty pleasures) of the globalized cultural-industrial complex, you really can’t beat the view from a museum on the fifty-third floor, in a building in which the opening dinner, conference, and hotel are all in spaces owned by the same family and accessible by the same elevator.

The scene at the Italian buffet dinner (Roppongi Hills Club, 51/F) that followed resembled a night in Ai’s now-shuttered restaurant, Qu Na’r, circa 2005. Each impromptu table constituted an orb of affinity and interest, with groups falling into and out of alignment as the night wore on. Everyone wanted a piece of the bearded master, who in turn preferred to crack jokes in Chinese to his lieutenants, all of whom were outfitted in Issey Miyake purchased during a “thank-you” shopping spree at the end of twelve days installing. Around the room were Ai’s dealers—Urs Meile, Christophe Mao, Cheryl Haines, Marc Benda—and auction-house folks like Phillips de Pury’s Chin Chin Yap and Jeremy Wingfield and Guardian’s Xiaoming Zhang. A few collectors were there, too—Uli Sigg, Hallam Chow, Larry Warsh, and Greg Liu—along with some museum people, including a MoMA delegation, of which newly minted curator Doryun Chong was a part. With unflagging precision, Kataoka announced the party’s imminent end at the fifteen-, ten-, and five-minute marks, giving just enough time to down an espresso and regroup for another outing on the plaza below, in the shadow (cast by a perfectly calibrated spotlight, twenty stories above) of a giant Louise Bourgeois spider.

Sunday (Academy Hills, 49/F) saw an eight-hour “interview marathon”—yes, it seems the Obristian coinage has entered the public domain—as six interlocutors (myself included) tag-teamed the artist with interpretations of his work, exhortations on their own, and, sometimes, good questions. Sigg led off with a condensed history of Chinese contemporary art, illustrated with images drawn entirely from his encyclopedic collection. Architect Kengo Kuma posed questions of “craftsmanship,” an issue that seemed to haunt the curatorial premise of the show upstairs. Artist Hiroshi Sugimoto, like Ai a self-taught architect, closed the day’s events with a lengthy encomium to his own recent projects, including a museum he designed and the first show—“naturally of my own work”—to be staged there. “Will there be a second show?” Ai rejoined.

Not surprisingly, the conversation often came back to Ai’s recent brush with the law that led to the closure of his much-loved blog in early June. He jovially recounted a tale of calling the Caochangdi village police station to report the secret agents who were staking out his home and studio and who refused to show him their badges. (One of the plainclothes turned out to be the brother of the local patrolman—so much for that plan.) Many speculate that the troubles owed ultimately to the “citizen’s investigation”—staffed by volunteers and mobilized via his blog—that canvassed the Sichuan disaster zone throughout the spring, collecting names and vital statistics on fifty-one hundred of the earthquake’s youngest victims. For Ai, the unresolved carnage—60 percent of parents have not been able to reclaim their children’s remains—owes much to shoddy school construction, and thus to party corruption. Under this pressure, the government released a figure of 5,335 dead schoolchildren just before the one-year anniversary of the May 12 quake. Asked point-blank by architect Shigeru Ban why he bothered to pursue this seemingly self-destructive personal campaign, Ai looked around at the hundreds of eyes fixed on him and replied bluntly, “If I don’t use my social privilege to do this, I feel ashamed.” |

Merce Cunningham, Event, 2009. Performance views, Rockefeller Park, New York. Presented by River to River Festival and Joyce Theater. August 1–2, 2009. Dylan Crossman, Daniel Madoff, Andrea Weber, Silas Riener, and Brandon Collwes. (All photos: Ryan McNamara)

ON AUGUST 1 AND 2, less than a week after Merce Cunningham’s death, members of his company gathered in Lower Manhattan to perform their first scheduled piece since his passing: the last, presumably, of the legendary site-specific Events to have been overseen by the choreographer. Over the course of those two days, in a small wedge of park between the gleaming postmillennium luxury condominiums (with names like the Solaire, the Riverhouse, and—perhaps appropriately—Tribeca Pointe) and the glistening waters of the Hudson, more than a thousand people sat in the grass around two small stages—one farther northeast, the other closer to the river—to partake in what had become, by default, an impromptu Cunningham memorial.

A number of former Cunningham disciples—many now major choreographers in their own right—were present for Saturday evening’s performance, given under an appropriately estival clear blue sky. Yvonne Rainer had staked out a space in the grass between the two stages, while Steve Paxton sat a bit north. Karole Armitage was there, as was the artist Charles Atlas, who got his start as Cunningham’s videographer. Younger choreographers, such as Sarah Michelson, Jack Ferver, and Jonah Bokaer (also a former Cunningham dancer, and the founder of the dance space Chez Bushwick), came to pay homage over the course of the two nights (a third performance in between the two had to be canceled due to the rain), as did art dealers Carol Greene and Janice Guy, artists Vera Lutter and Matthew Buckingham, and the art historian Douglas Crimp.

The dancers performed on both platforms, moving in between the two via a long path cordoned off in the grass. It was impossible to see everything; the split stages (with the northeast devoted more to solos and the southwest largely to ensembles) thwarted scopophilia, just as the multidirectional dancing destabilized any illusions of omniscient viewing. If dance is already an ephemeral medium, the dismantling of traditional sight lines makes it infinitely more so. “The Cunningham challenge,” as Lutter sagely put it.

The Event rose to the occasion; could it have been any other way? “Indescribable,” Paxton accurately described it. The characteristic Cunningham tics—if such a relentless innovator could be said to have any—were prevalent: the isolated, often incongruous choreography for different bodies (or even different parts of the same body); the unexpected shifts in style and tempo, executed according to a logic known only to the dancers; the swift, stage-consuming lateral movements. There’s a great deal of running—or an approximation of running, quick and utilitarian, often with arms slightly raised but parallel to the body (sometimes, to me, evoking action figures). There are frequent moments in relevé, and though the dancers are always extraordinarily composed and purposeful, strain is never obscured. Cunningham’s style influenced everyone, but here was evidence that the style itself remains inimitable. (Much of this may have to do with his dancers; he left behind an incredible company—perhaps the best in the world.)

Because of the fleetingness of it all, I found myself clinging to certain phrases harder than usual. (A favorite, which I remembered from the final Beacon Event in May, featured Andrea Weber in demi-pointe, with one hand extended above and one below; she held it for an excruciating amount of time, until Brandon Collwes, the tattooed perfectionist, arrived at her side to relieve her, beginning their own intimate partnering.) Sitting up close, just a few feet from the stages, it was impossible not to fall under the sway of individual dancers; everyone’s a soloist, each one impossibly gifted. When Weber isn’t smiling it looks as though she is, and when she is she’s practically beaming; the chiseled Silas Riener often has a stoic, faraway look, and at least once Weber patted him as she left the stage, as if to console him.

Roughly two-thirds of the way through the Event, the dancers paused to perform the three “still” movements of 4'33", which Cunningham planned as a memorial to John Cage but which became an uncanny tribute to Cunningham as well. The choreography was indeterminate, which meant the dancers could choose any pose they liked—Riener said that he had known only that he simply wanted to “face the water”—and at the end of the final movement, as dancers took to the warm-up area adjacent to the stage, many were crying.

According to Calvin Tomkins’s 1968 New Yorker profile on Cunningham, Alice B. Toklas had approached the choreographer after a 1949 recital and told him she liked his dancing “because it’s so pagan.” This comment came to mind while watching the movement on the westernmost stage, which at times did seem to exude a peculiar jocularity, featuring numerous ritualistic and presentational gestures. Near the end of the performance, on that same stage, Weber, Emma Desjardins, and Marcie Munnerlyn performed a mesmerizing adagio trio, which was followed by three male dancers—Riener, Collwes, and the new Dylan Crossman (one of two fresh-faced but exceptional dancers who joined the company a mere two weeks ago)—who leaped around variously like mantises, their arms curving inward, or exuberant cranes, arms extended. The dance ended, as Crimp noted, with the same, climactic sequence that marked the conclusion to the fourth Beacon Event, with all eleven dancers—eight on one stage, three on the other—dancing in unison. (“A finale worthy of Petipa or Balanchine,” he wrote last year.)

On Sunday, the loss seemed doubly painful; there would never be another new Cunningham Event. Seated on a platform to the east, next to Cunningham’s longtime archivist David Vaughan, was Alastair Macaulay, the Times’s chief dance critic, in tears. “Bravo,” he mouthed. Bravo. The dancers filed solemnly out of the park, and the crowd dispersed in the gloaming. |

THESE SOUNDS ARE MADE by Curtis Rhodes’s granular application, which was modeled after the way I patched the Buchla Box.” “To get the ‘pingy-y’ tones, I frequency-modulated the pitch of the oscillator from zero to maximum.” If Morton Subotnick’s explanations of his innovations in computer-generated sound occasionally resembled a geeky version of Spinal Tap guitarist Nigel Tufnell’s immortal claim, “These go to eleven,” his Friday-night performance at Brooklyn’s Issue Project Room confirmed him as an altogether more serious artist than his mock-rock counterpart. That said, the cherubic seventy-six-year-old composer was far from po-faced, and he clearly relished the opportunity to reinterpret some vintage material for a younger crowd.

Subotnick’s slot was the last in Issue Project Room’s Floating Points Festival, an annual monthlong series designed around its custom-made fifteen-channel hemispherical speaker system (other performers included Hisham Bharoocha, Stephen Vitiello, harpist to the stars Zeena Parkins, and the omnipresent Tony Conrad). Manipulating (“what they nowadays call ‘remixing’”) his 1967 debut recording, Silver Apples of the Moon, and 1978’s A Sky of Cloudless Sulfur, Subotnick also made sure to provide exhaustive context for the newbies. Recalling at length his first encounter with the boss of Nonesuch Records (“I threw him out. I thought he was making fun of me!”), and the incongruous commercial success of his 1969 quadraphonic disc Touch (“It sold a lot because there was nothing else to play on that system at the time”), he radiated an amused awareness of the unpredictability of a career defined by journeys into uncharted waters.

“This is my third attempt at this,” Subotnick revealed, introducing Silver Apples. “I have a year to figure it out before I take it on tour. You’re the guinea pigs.” But after fifteen minutes of beguiling music that snaked around the room, continually splintering and reforming as its maker tweaked some sounds and interjected others, we felt like more than mere test subjects. “I sort of understand why people were writing me letters saying they saw little green men coming into their houses after hearing that,” the composer chuckled. A Sky, to these ears, was better yet, a symphony of drips, rustles, clonks, and tweets that built to a steady pulse before trailing away to enthusiastic applause. For a man once dismissed by Time magazine as “a tone-deaf mute,” it was a quiet triumph.

Such are the pleasures of the art-world off-season: One night you’re at an intimate gathering of fifty-odd cognoscenti, the next you’re among a reported 71,500 souls packed into All Points West. And at the three-day rock binge, which reached its midway point at New Jersey’s Liberty State Park the following evening, hearing damage was a real possibility. But the danger didn’t end there. Trudging through the mire toward the main arena, my companion and I were nearly mowed down by a van containing a deadpan Adrian Grenier, then a couple of minutes later found ourselves in the path of Courtney Love, leaping from a trailer in the direction of a nearby taco stand. Once equipped with the requisite rainbow of plastic wristbands, we followed My Bloody Valentine’s Kevin Shields self-consciously onto the stage, the guitarist joining his bandmates front and center for a characteristically immersive set as we secreted ourselves in the wings. And even with the benefit of earplugs, it was clear that they really could play “one louder” than ten. |

18.07.2009

ARCH ENEMY (Swe)

SODOM (Ger)

VADER (Pol)

LAKE OF TEARS (Swe)

HEAVEN SHALL BURN (Ger)

DEADLOCK (Ger)

HELL:ON (Ukr)

FRAGILE ART (Ukr/Rus)

KHORS (Ukr)

HIERONYMUS BOSCH (Rus)

EMPTY PLAYGROUND (Pol)

MIND:|:SHREDDER (Ukr) 19.07.2009

DORO (Ger)

CARCASS (Uk)

STRATOVARIUS (Fin)

GRAVE DIGGER (Ger)

ROTTING CHRIST (Gre)

FINNTROLL (Fin)

DARZAMAT (Pol)

W.H.I.T.E. (Ukr)

MORIA (Ukr)

NATURAL SPIRIT (Ukr)

SYSTEM KORR (Ukr)

GRIMFAITH (Ukr) |

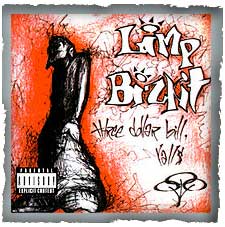

The original line-up of Limp Bizkit is back, do you believe in miracles? If so, then you can believe Limp Bizkit is back to do it ALL again! Album! Tour! Worldwide!

(New York, NY) February 12, 2009 – The original line-up of Fred Durst, Wes Borland, Sam Rivers, John Otto, and DJ Lethal are back from an eight year hiatus to bring their world back to ours. Fred Durst and Wes Borland said in a joint statement:

"We decided we were more disgusted and bored with the state of heavy popular music than we were with each other. Regardless of where our separate paths have taken us, we recognize there is a powerful and unique energy with this particular group of people we have not found anywhere else. This is why Limp Bizkit is back."

The guys will kick off a world tour in the Spring on the overseas festival circuit with headline shows sprinkled in throughout Eastern Europe and Europe, selected dates include, in late May, Russia, Ukraine, and the Baltic countries where Limp Bizkit has never played before despite huge demand, along with major festivals like Rock Am Ring and Rock Im Park in Germany, more dates to be announced shortly. A new album, which would be the original group’s first full-length effort since 2000, is also planned. Limp Bizkit’s first three albums have sold over 20 million copies in the U.S. alone, and another 13 million in the rest of the world. © www.limpbizkit.com |

Concert of progressive music bands:

1. Infinity Dreams (Kyiv, progressive heavy) - http://www.froster.org 2. Virgo (Херсон, progressive metal) - http://vkontakte.ru/club7818190 3. Chorna rada (Kyiv, progressive metal) - http://chornarada.com/ 4. Delia (Київ, sympho metal) - http://www.delia.com.ua/ 5. Zabuta Simfinia (Poltava, cosmocore) - http://www.forsym.net/ Concert will be at clube "Queen Bee"

http://savepic.ru/462203.jpg

В цей вечір для вас гратимуть:

1. Infinity Dreams (Київ, progressive heavy) - http://www.froster.org/modules.php?name=Bands&op=band&band_id=590

2. Virgo (Херсон, progressive metal) - http://vkontakte.ru/club7818190

3. Чорна Рада (Київ, progressive metal) - http://chornarada.com/

4. Delia (Київ, sympho metal) - http://www.delia.com.ua/

5. Забута Симфонія (Полтава, cosmocore) - http://www.forsym.net/

Концерт відбудеться у клубі Queen Bee (вул. Маршала Малиновського, 5 – ст.. метро «Оболонь»).

Початок – 18.00. Вхід – 30 грн. (попередній продаж), 40 грн. (в день концерту).

З питань попереднього придбання квитків та акредитації преси – звертайтеся за телефонами:

8 050 777 65 86 (Саша)

8 093 487 76 48 (Вова)

або на email: nedeliaev@gmail.com

Links:

http://savepic.ru/510329.jpg - afisha

http://savepic.ru/462203.jpg - map |

|

| Statistics |

Total online: 1 Guests: 1 Users: 0 | |